OPINION

Tinubu And The Echoes Of Two Saints Lucia And Helena

Valentine Obienyem*

Napoleon Bonaparte, a Corsican-born general, is one of history’s most compelling figures, a man whose life defied the ordinary and whose death has left an indelible mark. For those who appreciate the scope of history, the story of Napoleon is difficult to read without pausing in awe. During his prime, he dominated Europe, redrawing borders, rewriting military doctrine, and attempting to conquer the world.

When Napoleon first fell from power in 1814, he was exiled to Elba, a small Mediterranean island. It was expected to be a quiet ending. But, in an astonishing move, he escaped from Elba, returned to France without an army, and rallied the country to his cause. Thus began the fabled Hundred Days, his brief second reign. The resurgence was decisively halted at the Battle of Waterloo, which took place in a small Belgian town. Because of the linguistic odyssey that characterises philology, the name has become synonymous with final, crushing defeat. “To meet one’s Waterloo” now refers to confronting a long-awaited reckoning.

Napoleon surrendered to the British after being defeated and attempting to flee to the United States. They exiled him to the remote island of Saint Helena, located in the vast South Atlantic Ocean. Britain regarded Saint Helena as ideal for isolating a troublemaker. Far from any sympathetic power, inaccessible to his admirers, and secure enough to ensure that the once-unrivalled Emperor would never disrupt European peace again.

Napoleon spent his last years on that lonely outpost. Life there was bleak. Rats scurried throughout his quarters, even nesting in his hat. Fleas and bugs made no distinction between human rank, and the island’s climate and isolation ravaged both body and spirit. Despite his despair, he rediscovered his Catholic faith, arranged for Sunday Masses at his home near the end of his life, and received the sacraments two days before his death. He was buried on the island, but in 1840, his remains were returned to France and interred with full honours at Les Invalides in Paris. In his will, he stated, “I wish my ashes to rest on the banks of the Seine, amidst the French people whom I loved so much.” Years later, during a visit to Paris, I stood in front of that very tomb in Les Invalides, inspired by my admiration for Napoleon. Nearby, the Seine flows quietly, fulfilling the final wish of a man who once set Europe on fire.

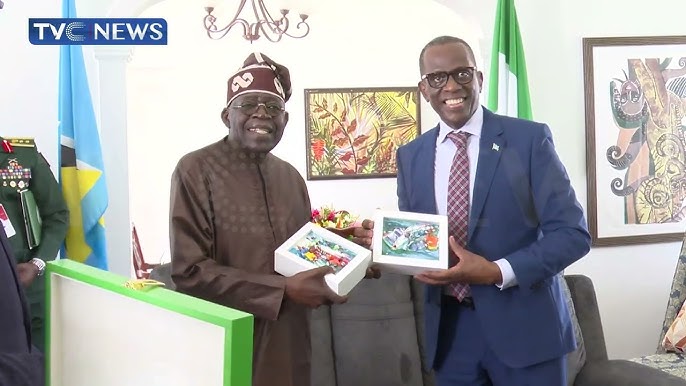

Why bring up Napoleon and Saint Helena now? Because President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s recent trip to the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia prompted a curious reflection. While the circumstances are obviously different, the justifications for Napoleon’s exile and Tinubu’s retreat are eerily similar in logic. Napoleon’s captors justified his exile on the basis of necessity and distance. They saw isolation as a form of peacekeeping. Similarly, following a barrage of attacks from concerned Nigerians, Tinubu’s handlers have explained that his presence in Saint Lucia, despite ongoing domestic crises, is not for leisure but for diplomatic purposes. They proposed that the visit would strengthen bilateral ties with a country with significant Nigerian ancestry while also serving as a study tour for tourism development.

Of course, such rationalisation is not unique to Nigeria or its leaders. Throughout history, powerful men have used convenient excuses to justify controversial actions. Julius Caesar once broke with Roman tradition by sitting down to receive senators, which was viewed as disrespectful and imperious. When challenged, he explained that he had a runny stomach and that standing might cause an unfavourable movement – as we would say in Igbo, “nwoke anyụa nsi ọkụ” (a man releasing hot diarrhoea). The excuse, however graphic, fooled no one. Most observers recognised it as a symbolic declaration: Caesar was no longer first among equals; he was already acting like a monarch.

Unlike many of his counterparts around the world, President Tinubu appears to prefer foreign retreats, including London, Paris, and now Saint Lucia. In contrast, many world leaders choose to vacation within their own countries, demonstrating not only modesty but also a symbolic sense of solidarity with their people and land. Presidents of the United States prefer Camp David. French President Emmanuel Macron spends the summer at Fort de Brégançon, the presidential retreat on the Mediterranean. Russian President Vladimir Putin famously unwinds in the Siberian wilderness, projecting an image of rugged nationalism. King Charles III of the United Kingdom continues the royal tradition of spending the summer at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. Germany’s President Frank-Walter Steinmeier takes quiet breaks in the Bavarian Alps, while Brazil’s President Lula da Silva retreats to Bahia, a region rich in Afro-Brazilian heritage. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi seeks spiritual solitude in the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand, while China’s President Xi Jinping retreats to Beidaihe, a coastal enclave for Communist Party elites. Even the Japanese Imperial Family spends their summers at their villa in Nasu, located deep in Tochigi Prefecture. During my trip to Rome, I visited the Papal retreat at Castel Gandolfo.

These are not casual choices; they reflect deliberate political symbolism, affirming the leader’s rootedness in the soil and soul of their country. In President Tinubu’s case, the pattern paints a different picture. His continued preference for foreign locations gives the impression of detachment. This was one of the reasons why purchasing a new presidential jet was considered a national emergency. As I write, he is still in Saint Lucia. Not even the metaphorical fires engulfing Nigeria – spiralling inflation, insecurity, power outages, and a cost-of-living crisis – nor the actual fires started by bandits and herdsmen would compel him to shorten his journey.

And so we return to Saint Helena. If remoteness is the standard for presidential retreats, perhaps President Tinubu will consider it for his next vacation. Saint Helena is peaceful and mysterious, and it has historically been home to powerful men. No crowd would rush to see him. It would provide a level of solitude that Saint Lucia cannot match. For a man tasked with leading a troubled country, it may just be the kind of quiet that forces reflection and, possibly, rebirth.

So, if remoteness is the new measure of presidential responsibility, and escapism has taken the place of governance, President Tinubu may consider other equally obscure yet geographically satisfying sanctuaries after Saint Helena. There is Saint Croix, a sleepy dot in the United States Virgin Islands. Alternatively, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, a foggy French territory clinging to the edge of North America, should think like Tinubu in terms of policy and governance. These islands, like Saint Lucia, provide the one thing our president appears to value most during national crises: distance, not just in miles, but in meaning.

-

CRIME3 years ago

PSC Dismisses DCP Abba Kyari, To Be Prosecuted Over Alleged $1.1m Fraud

-

FEATURED4 years ago

2022 Will Brighten Possibility Of Osinbajo Presidency, Says TPP

-

FEATURED2 years ago

Buhari’s Ministers, CEOs Should Be Held Accountable Along With Emefiele, Says Timi Frank

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY2 years ago

Oyedemi Reigns As 2023’s Real Estate Humanitarian Of The Year

-

SPORTS1 year ago

BREAKING: Jürgen Klopp Quits Liverpool As Manager At End Of Season

-

SPORTS2 years ago

Could Liverpool Afford Kylian Mbappe For €200 million? Wages, Transfer Fee

-

ENTERTAINMENT2 years ago

Veteran Nigerian Musician, Basil Akalonu Dies At 72

-

FEATURED2 years ago

Tribunal Judgement: Peter Obi Warns Of Vanishing Electoral Jurisprudence, Heads To Supreme Court

-

BUSINESS & ECONOMY2 years ago

Oyedemi Bags ‘Next Bulls Award’ As BusinessDay Celebrates Top 25 CEOs/ Business Leaders

-

FEATURED3 years ago

2023 Presidency: South East PDP Aspirants Unite, Demand Party Ticket For Zone